Best management guide

Chickpea production: southern and western region

Australian industry

Chickpea (Cicer arietinum) is a winter crop well suited to the medium rainfall (300–500 mm) areas of south-eastern Australia. Crop growth during winter months is very slow but accelerates in spring as the weather warms.

Chickpea is a high value pulse crop used almost entirely for human consumption. Attractive presentation of the grain product is of paramount importance.

In the southern region, chickpeas were first grown during the 1980s with the sown area peaking in the mid 1990s before ascochyta blight almost wiped the industry out. New varieties of chickpeas that are ascochyta resistant varieties are now available and the industry is growing once again.

There are two groups of chickpea – desi and kabuli – mainly distinguished by seed size, shape and colour. The two types have different production requirements, markets and end-uses. Most Australian chickpea (mainly desi type) production is in northern Australia, and nearly all of the grain is exported. Most kabuli production occurs in the southern region.

The main market for desi chickpea is India and Pakistan, and to Indian communities in other parts of the world (such as Britain and Western Canada). Buyers in India and Pakistan prefer larger, light coloured desi chickpea grain. Kabuli chickpea is marketed mainly to buyers in the Middle East and Europe.

Types

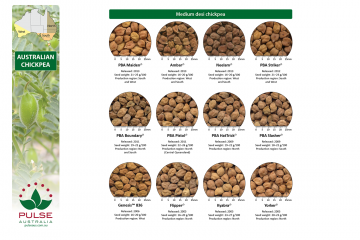

Desi types are generally earlier maturing and higher yielding than the kabuli types, particularly the larger seeded kabulis.

Desi chickpea

- Desi types have small angular seeds, each weighing about 120 mg, that are wrinkled at the beak and the different varieties range in colour including brown, light brown, fawn, yellow, orange, black or green seed.

- The grain is normally dehulled and split to obtain dhal and then may be further processed to produce flour (besan). Buyers in India and the sub-continent favour desi chickpea over kabuli.

- There is an increasing use of large, whole seeded desi types in a range of food preparations in Bangladesh. A small premium has been paid for desi types (e.g. Kyabra) fitting this use.

- Desi chickpeas have traditionally made up about 90% to 95% of Australian production.

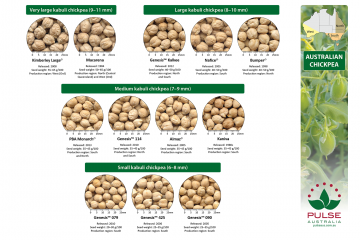

Kabuli chickpea

- Kabuli, sometimes called garbanzos, have larger, rounder seeds than desi types. Each seed weighs about 400 mg.

- They are white to cream in colour and are almost exclusively used whole. Buyers in the Mediterranean region prefer kabuli type chickpea.

- Within the kabuli types several market categories have emerged for Australian growers including the traditional large seeded kabuli markets, where large seed size (9 mm and above) is important to attract premium prices, a small seeded (7–8 mm) class than can be sold into bulk kabuli markets or graded to size to grade out the 8 mm class and a very small seeded class (less than 7 mm) than is sold into bulk kabuli markets.

Place in the rotation

Chickpea is a winter pulse crop well-suited to the southern grain production region, in rotation with cereal and canola crops. Following dun field pea or faba bean, leave two years before sowing chickpea. It is almost impossible to grade volunteer peas out of chickpea.

As a higher value crop, kabuli types are often grown on fallow where extra moisture can mean larger seed.

The 'pulse effect' on wheat yields and protein tends to be less noticeable after a chickpea crop than after other pulses. It is often better to follow chickpea with barley rather than wheat. While older chickpea varieties were a host for the root lesion nematode (Pratylenchus neglectus, P. thornei), newer varieties are not as susceptible to root lesion nematode multiplication.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

|

Chickpea prefer well drained loam to clay soils with a pH in the range of 6 to 8. They will not grow in light acid soils and areas prone to waterlogging should be avoided. Chickpea crops must be harvested close to the ground so stony paddocks or fields with uneven soil surface (e.g. gilgai) should be avoided.

Chickpea are susceptible to hostile sub-soils, with boron toxicity, sodicity and salinity causing patchiness in affected paddocks. Chickpea will not tolerate soils with any exchangeable aluminium present. Tolerance to sodicity in the root zone (to 90 cm) is less than 1% exchangeable sodium (ESP) on the surface and less than 5% ESP in the subsoil.

Broadleaf weeds and resistant grasses can cause major problems and a careful management strategy must be worked out well in advance. If possible, control weeds in the year prior to sowing chickpea or avoid paddocks with specific weeds that cannot be controlled by the available herbicides.

Foliar sprays of zinc and manganese may be needed if these deficiencies are identified.

Chickpea are not well suited to the lower rainfall, hotter areas, although the plants will set seed under warmer conditions where other pulse crops are likely to fail.

Cool wet conditions are more likely to stimulate foliar diseases and these can adversely affect seed set and yield.

Controlling ascochyta blight is a major consideration in chickpea. Variety choice, crop hygiene, fungicide choice and application timing are all important in an overall chickpea management strategy for ascochyta blight. Several varieties are now available that are resistant to ascochyta blight during the vegetative phases of the crop however all varieties remain susceptible to the disease during podding.

Provided ascochyta blight resistant varieties are used, delayed sowing is no longer necessary and strategic foliar fungicide use may only be required at podding. Susceptible varieties require fungicides to be applied regularly throughout the growing season.

Desi varieties should only be grown in areas where the annual rainfall is greater than 350 mm. Sowing is best carried out from early May to early June with early sowing recommended for the lower rainfall areas.

Kabuli varieties are later maturing and should only be grown in areas where the annual rainfall is over 450 mm.

For best results with chickpea, follow the recommendations in this guide wherever possible to minimise production risks and optimise the crop’s performance.

Keys to successful chickpea production

- Make chickpeas part of an integrated cropping system involving wheat, canola or barley. By taking a systems perspective and assess financial performance over several seasons you can estimate the true benefits of chickpeas in a rotation.

- Choose the right variety based on long term yield data for your region, maturity, disease resistance and the market opportunities for human consumption.

- Use good quality seed with high germination (80%+) and vigour that is free from seed-borne ascochyta and botrytis infection.

- Select and manage paddocks well in advance to control weeds and retain crop residues. Select paddocks with free draining soil of more neutral pH and low sodicity, salinity and boron toxicity. Herbicide residues need to be considered, as well as likely weed pressure and the ability to effectively control weeds before seeding and in-crop.

- Establish sufficient plants as recommended for the variety, situation and sowing time. Ideally ground cover should coincide with the time pod filling begins. Plant populations can range from 30–50 plants/m2 for rain-fed crops or higher if sown late.

- Sow on time. Sowing time is critical and regional recommendations should be followed. Late sowing reduces yield potential by lowering crop biomass, shortening the pod-filling period and increasing risks from moisture stress and high temperatures. Early sowing can lead to bulky crops, poor early pod set and greater disease risks.

- Ensure good nutrition. Nitrogen (N) fertiliser is unnecessary as the crop’s N requirement will be met through symbiotic fixing of atmospheric nitrogen, provided the seed is inoculated at sowing with the correct commercially available rhizobia inoculant. On phosphorus (P) deficient country, apply fertiliser at rates similar to or slightly less than those for wheat. On alkaline clay soils, fertilising with zinc may be warranted. On acid soils, molybdenum may be deficient and should be applied at or before sowing.

- Know the disease threats to chickpea and how to manage them for your district. No varieties are resistant to all fungal and virus diseases. The major risks are ascochyta blight, botrytis grey mould and plant viruses. The impact of fungal diseases on yield can be diminished through the strategic selection and use of fungicides and crop management. Maintain an isolation distances of more than 500 m from the previous year’s chickpea stubble, and eradicate volunteer plants over summer and autumn as these plants are a source aphids (potential plant virus vectors) and disease inoculum.

- Control insect pests such as aphids and helicoverpa. Controlling the ‘green bridge’ of weeds and volunteer crop plants over summer can reduce aphid populations and reduce the numbers that can infest the crop in the early growth stages. Monitor for helicoverpa (native budworm) caterpillars is essential during podding. Caterpillar feeding during podding will affect yield and potentially render the seed unsuitable for human consumption markets.

- Harvest on time, with a properly set-up header. Start harvesting when the seeds in the majority of pods ‘rattle’. Stems may not be completely dry at this stage. Pods will thresh easily to yield clean, whole seeds with a minimum of splits and cracks provided the header settings are correct.

- Have a marketing plan that includes plans for on-farm storage or delivery options off-header. Investigate forward contracting if storage, pools or warehousing is not an option.

- Optimise irrigation set-up and timing. Chickpeas respond well to irrigation in dry areas. Furrow irrigation is preferred over over-head irrigation. If necessary, pre-water then sow. To maximise yield potential, irrigate crops to produce maximum biomass while avoiding over-watering as chickpea crops will not tolerate waterlogging. Do not allow the plants to stress during flowering and pod-fill.

Plant physiology

Chickpea germination is hypogeal, with the cotyledons remaining below the soil surface. This enables it to emerge from sowing as deep as 15 cm. In arid regions, chickpea is sown deep as surface moisture is often inadequate to allow adequate crop establishment.

The chickpea plant is erect and freestanding, usually 15–60 cm in height, although well-grown plants may grow to 80 cm. The plants have a fibrous taproot system, a number of woody stems forming from the base, upper secondary branches and fine, frond-like leaves.

The node from which the first branch arises on the main stem above the soil is counted as node one. In chickpeas, alternate primary branches usually originate from nodes just above ground level (usually one to eight primary branches on the main stem, depending on growing conditions). A node is counted as developed when 6–15 leaflets have unfolded and flattened out.

Each leaflet has a thick covering of glandular hairs that secrete a strong acid (mostly malic acid), particularly during pod-set. The malic secretions from all vegetative surfaces of the plant seem to play a role in protecting the plant against pests such as red-legged earth mite, lucerne flea, aphids and pod borers. Similar substances are also secreted from the root system and can solubilise soil-bound phosphate and other nutrients. The acid also corrodes leather boots.

Chickpea plants can derive more than 70 per cent of their nitrogen requirement from symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Chickpea roots develop symbiotic nodules with the Rhizobium bacteria, capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen. The plant provides carbohydrates for the bacteria in return for nitrogen fixed inside the nodules.

These nodules are visible within about a month of plant emergence, and eventually form slightly flattened, fan-like lobes. Practically all nodules are confined to the top 30 cm of soil and 90% are within the top 15 cm of the profile. When cut open, nodules actively fixing nitrogen have a pink centre. Nitrogen fixation is highly sensitive to waterlogging so it is essential that chickpea crops are grown on well aerated and drained soils.

Yields are best in areas with reliable winter rainfall for crop growth and mild spring conditions during seed filling. Chickpea is well suited to well-drained, non-acidic soils with medium to heavy clay texture.

Chickpeas are considered very indeterminate in their growth habit, i.e. their terminal bud is always vegetative and keeps growing, even after the plant switches to reproductive mode and flowering begins.

Temperature, day length and drought are the three major factors affecting flowering in chickpea. Temperature is generally more important than day length. Flowering and pod set in chickpea requires an average daily temperature of 15°C and cool wet conditions at flowering can adversely affect pod and seed set. Flowering is invariably delayed under low temperatures but more branching occurs.

Progress towards flowering is rapid during long days (17+ hours) and flowering is delayed but never prevented under short day (<17 hrs) conditions.

Chickpeas, unlike other cool season legumes, are very susceptible to cold conditions. This is particularly so at flowering and any advantage derived from early flowering is often negated by increased flower and pod abortion due to late frosts or cold snaps. Pods at a later stage of development are generally more resistant to frost than flowers and small pods, but may suffer some mottled darkening of the seed coat.

Last updated: 20 November 2015