Australian Pulse Bulletin

Chickpea: Managing botrytis grey mould

Mal Ryley1, Kevin Moore2, Gordon Cumming3, Leigh Jenkins2

1 Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, 2 NSW Department Primary Industries, 3 Pulse Australia.

Background

Botrytis grey mould (BGM) in chickpea is caused by the fungus Botrytis cinerea. B. cinerea is a significant pathogen of pulse crops particularly lentils, ornamental plants grown under glasshouse conditions, and fruit, including grapes, strawberries and apples. Flowers are especially vulnerable to BGM infection. B. cinerea does not infect cereals or grasses.

In the northern GRDC region, B. cinerea has been recorded on over 138 genera of plants in 70 families. Legumes and asteraceous plants comprise approximately 20% of these records. As well as being a serious pathogen, B. cinerea can infect and invade dying and dead plant tissue. This wide host range and saprophytic capacity means inoculum of B. cinerea is rarely limiting. If conditions favour infection and disease development, BGM will occur.

This makes management of BGM different from chickpea ascochyta, which is more dependent on inoculum, at least in the early phases of an epidemic.

B. cinerea also causes pre and post-emergent seedling death. This happens when chickpea seed, infected during a BGM outbreak, is used for sowing. Seedling disease does not need the wet conditions that are usually required for infection and spread of BGM later in the crop cycle.

Symptoms

The first symptom of BGM infection in a crop is often drooping of the terminal branches. If groups of plants are infected, these may appear as yellow patches in the crop. The diagnostic feature is a grey 'fuzz' which, under high humidity, develops on flowers, pods, stems and on dead leaves and petioles.

Lesions can develop anywhere along the stem but are usually first found on the lower part of the stems often starting in leaf axils. Infected seeds are usually smaller than normal and are often covered with white to grey fungal growth.

When a severely BGM-infected canopy is opened, clouds of spores are evident (avoid inhaling these). During dry weather the 'fuzz' is not obvious, but it develops again when wet weather returns. Small, dark brown/black resting bodies (sclerotes) of B. cinerea may develop on infected dead tissue, and are capable of producing spores on their surface.

The stem lesions caused by BGM can be confused with those caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (at and above ground level) and by Sclerotinia minor (at ground level), but neither of these pathogens produce the grey 'fuzz' typical of BGM. Also, sclerotinia lesions tend to remain white, and are covered by a dense cottony fungal growth, in which irregular shaped black sclerotes develop.

In contrast, the sclerotes of B. cinerea are more rounded and usually develop after the stems die. They are smaller than the sclerotes of S. sclerotiorum, but larger than the angular sclerotes of S. minor.

-

If groups of plants are infected, these may appear as yellow patches in the crop. (Photo: Phil Davies)

-

The diagnostic feature is a grey 'fuzz' which develops under high humidity conditions. (Photo: Phil Davies)

-

Lesions can develop anywhere along the stem but are usually first found on the lower part of the stems often starting in leaf axils.

-

-

BGM on a chickpea flower. (Photo: Phil Davies)

-

-

Infected seeds are usually smaller than normal and are often covered with white to grey fungal growth.

Biology and epidemiology

B. cinerea produces diffuse white fungal growth which later turns grey due to the production of huge numbers of spores borne in clusters at the ends of dark stalks.

Over 10 million spores can be produced on a single 2 cm long lesion on a chickpea stem. Consequently, B. cinerea has the capacity to rapidly develop during conducive weather conditions. The spores can be blown many kilometres, and if deposited on chickpea plants they can remain dormant until conditions favour spore germination.

Free moisture is necessary for germination and infection. Lesions and the grey 'fuzz' are evident 5–7 days after infection under ideal conditions.

B. cinerea is favoured by moderate temperatures (20-25°C) and frequent rainfall events. It does not become a risk until the average daily temperature (ADT) is 15°C or higher. The combination of early canopy closure, prolonged plant wetness and overcast weather results in high relative humidity and rapid leaf death in the canopy, conditions which are ideal for B. cinerea.

B. cinerea can survive on and in infected seeds, in infected stubble, on alternative hosts, in dead plant tissue and as sclerotes. The relative importance of these in Australia is unknown, but recent research in Victoria demonstrated that B. cinerea can survive for up to 18 months on infected stubble under field conditions. Other research from Western Australia suggests that sclerotes of B. cinerea cannot survive over summer because they lose their viability during hot weather.

Factors that contribute to a BGM epidemic

Factors that favour infection and spread of BGM in favourable seasons include:

- early sowing (mid April to early May) and narrow rows

- frequent overcast, showery weather

- limited supply of effective fungicides

- lack of BGM tolerant/resistant varieties

High biomass crops and early canopy closure often results in high in-crop humidity and poor penetration of fungicides. If the crop becomes lodged the situation is exacerbated.

Rainy weather not only favours the disease but wet paddocks also limit the spray opportunities for ground rigs.

Following a season where widespread BGM infection has occurred in a district there is often a shortage of disease-free seed for planting and there is a high quantity of infected crop residue across a large area. Both of these factors will increase the disease risk for the following year. Whether BGM becomes a problem the following year will depend on seasonal conditions.

Management options

Stubble management

It is likely that the pathogen can remain viable and capable of survival for as long as infected stubble remains on the soil surface. Burial of stubble removes the ability of B. cinerea to produce spores that can be blown around, and increases the rate of stubble breakdown by soil microbes.

Although burning of infected residues will also significantly reduce the amount of infected residues on the soil surface, it will not guarantee freedom from BGM in the following season.

Burying or burning stubble can significantly increase the risk of soil erosion and reduce water infiltration.

Volunteer control (the green bridge)

Volunteer chickpea plants growing in or near paddocks where BGM was a significant problem are a likely method of carry-over and must be managed by application of herbicide or cultivation.

This will also reduce carryover of ascochyta.

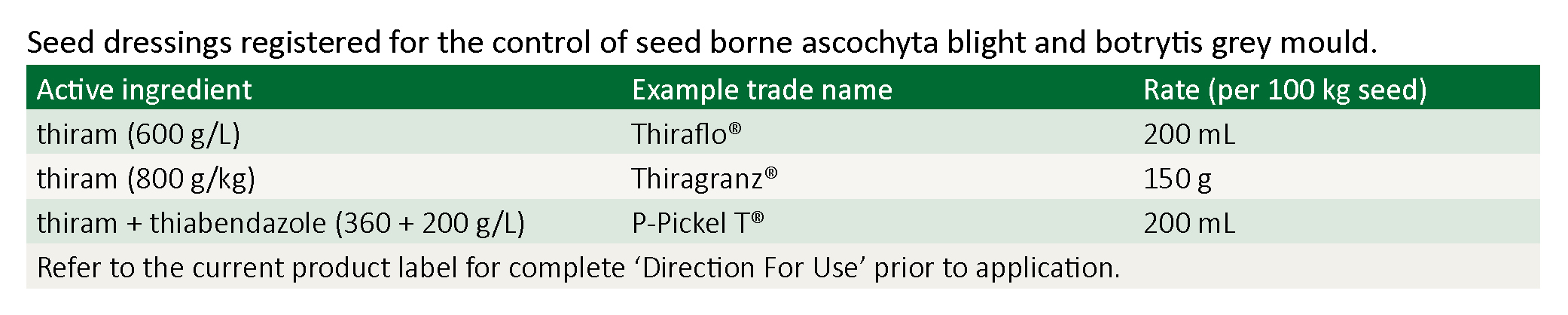

Seed source and treatment

Obtain seed from a commercial supplier, or from a source known to have negligible levels of BGM. Irrespective of the source, all seed must be thoroughly treated with a registered fungicide seed dressing.Thiram based fungicide seed dressings are effective in significantly reducing, but not entirely eliminating, BGM from infected seed.

Seedling emergence

Research on harvested seed has shown a germination test does not accurately predict emergence. Accordingly, growers are advised to conduct their own emergence test, as follows:

- After grading and treatment, sow 100 seeds at least 5 cm deep in the paddock that you intend for chickpeas and water if necessary.

- Count the number of seedlings that have emerged after one, two and three weeks and note their appearance. Do they look healthy or are they stunted and distorted.

- If you want to get an idea of variability in emergence and the paddock, replicate the test i.e. sow 100 seeds in 3-4 different locations in the paddock. This will also help identify potential herbicide residue problems.

Paddock selection

Paddocks in which chickpeas were affected by BGM should not be re-sown to chickpea, faba bean or lentil the following season. Nor should chickpea be sown beside paddocks where BGM was an issue the previous season.

As for ascochyta blight, chickpeas should be grown as far away from paddocks in which BGM was a problem as is practically possible.

However, under conducive conditions, this practice will not guarantee that crops will remain BGM free, because of the pathogen's wide host range, ability to colonise dead plant tissue, and the airborne nature of its spores.

Sowing time and row spacing

If long-term weather forecasts suggest a wetter-than-normal year (La Nina), consider sowing in the later part of the suggested sowing window for your district and on wider rows (e.g. 100 cm). Planting on wider rows results in increased air movement through the crop and reduced humidity within the canopy.

Varietal resistance

All current commercial varieties suitable for the northern region are susceptible to BGM, although Howzat is reported to have slightly better resistance than other varieties.

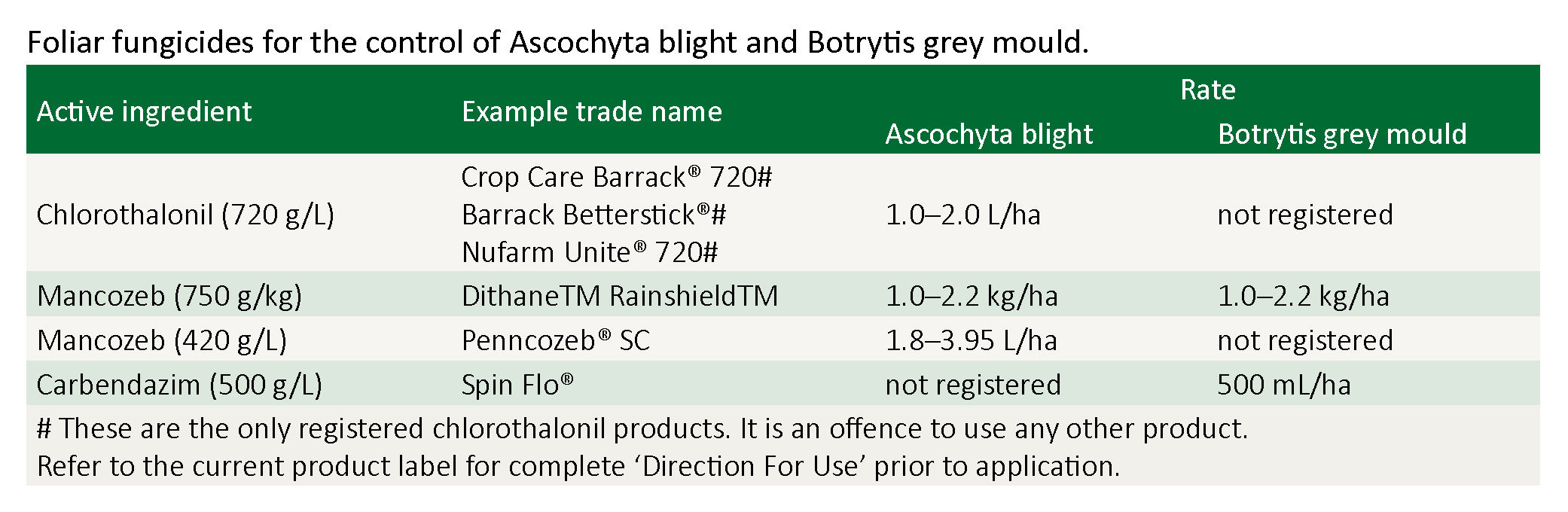

Foliar fungicides

In areas outside central Queensland, spraying for BGM is not needed in most years.

However, in seasons and situations favourable to the disease, a preventative spray of a registered fungicide immediately prior to canopy closure, followed by another application 2 weeks later, will assist in minimising BGM development in most years.

If BGM is detected in a district or in an individual crop, particularly during flowering or pod fill, a fungicide spray should be applied before the next rain event.

None of the fungicides currently registered or under permit for the management of BGM on chickpea have eradicant activity, so their application will not eradicate established infections. Consequently, timely and thorough application is critical.

More detailed information: Insert link to page title

Useful resources

- Chickpea: Sourcing High Quality Seed

- Chickpea: Effective Crop Establishment

- Integrated disease management in chickpea

- Chickpea best management guide—Northern region

- Chickpea best management guide—Southern region

Key contacts

Disclaimer

Information provided in this guide was correct at the time of the date shown below. No responsibility is accepted by Pulse Australia for any commercial outcomes from the use of information contained in this guide.

The information herein has been obtained from sources considered reliable but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. No liability or responsibility is accepted for any errors or for any negligence, omissions in the contents, default or lack of care for any loss or damage whatsoever that may arise from actions based on any material contained in this publication.

Readers who act on this information do so at their own risk.

Copyright © 2015 Pulse Australia

All rights reserved. The information provided in the publication may not be reproduced in part or in full, in any form whatsoever, without the prior written consent of Pulse Australia.

Last updated: 20 November 2015